A facility’s EAP is imperative to worker safety, of course, and can likely handle contained events, like fires. But what about a chemical release? A natural disaster? A terrorist threat? Evacuation might not always be the best response to a given emergency; consequently, the ability to provide real-time planning and response is becoming ever more important.

Incident Management

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) recommends that all business have an Incident Management System (IMS). An IMS, as outlined in NFPA 1600, has a combination of facilities, equipment, personnel, procedures and communications operating within a common organizational structure and is designed to aid in the management of resources during incidents.

As one part of a solid IMS, an Incident Command System (ICS) should be identified, similar to how an Emergency Response Team is identified in an EAP. The ICS puts a detailed plan in place to create more organized and streamlined efforts, which can ultimately minimize disruptions to operations, save lives , lessen damage and/or loss, and protect surrounding communities. In addition, it also allows the company to understand the total cost of risk.

Developing an Incident Management System

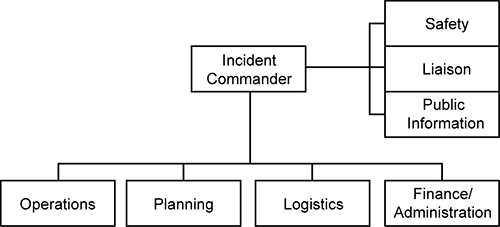

When developing an IMS, one should understand that the use of ICS depends upon the size and complexity of the business. Functions and roles may be assigned to multiple individuals or a few persons may be assigned multiple responsibilities. Figure 1 is a great example from FEMA of what the ICS might look like:

The Incident Commander should not only know what is happening/has happened, but he/she should understand what could happen next. They should be able to easily identify and answer questions such as:

- What type of incident is it?

- Who should be notified? Why?

- Which areas require evacuation or a shelter-in-place? Why?

In addition, the incident commander should take into account worker/responder exposure monitoring during the emergency, as well as any potential offsite impact.

When creating an IMS, one should consider automated solutions for incident management. Emergency management software, coupled with strategically placed chemical and meteorological sensors, allows incident commanders to respond to emergencies faster, more accurately, and in real-time with data provided by live plume models, release-rate estimations, meteorological data, and so much more.

Practice, Practice, Practice

The importance of emergency preparedness—conducting regular drills and identifying corrective actions—cannot be stressed enough. If workers and contractors do not know what actions to take or where to go, then the plan does no one any good.

Remember, drills combat human behavior, and there are a number of factors that affect human behavior during an emergency, including a person’s assumed role, experience, education, and personality, as well as the emergency’s perceived threat and the actions of others sharing the experience. Drills give employees and contractors experience, allowing them to react accurately, faster and more effectively in case of an actual emergency.

To learn more about Total Safety and its unwavering commitment to ensure the safe wellbeing of workers worldwide, contact them at 888.44.TOTAL or at mail@totalsafety.com.